Apr 19 2022

Apr 19 2022Notes From the Field: Western Screech-Owl

The forest around us is dense with accumulated life. Big ancient cedars are almost completely obscured by towering salal, huckleberry, and hemlock saplings, and every surface is a tiny emerald garden of moss, liverworts, and lichens. Above the canopy of the forest, the sky is blue and the sun is shining with no hint of rain, but here we are, soaked in the dripping understory of the old-growth rainforest. Jeremiah and I might as well be inside a green cloud.

Somewhere in all this exuberance of green, we think there is a threatened species of owl. These birds are nearly impossible to locate by day, so we are deploying automated recording units to passively record all the sounds of the forests for the next few months. When we recover these devices, we will scan the recordings to see if they detected the calls of the owl we are searching for. Our work here is urgent: this ancient rainforest is inside a proposed cutblock, and it is at imminent risk of being turned into a barren stump field.

The owl we are looking for is called a Western Screech-Owl. The coastal subspecies of this bird are considered federally and provincially threatened, with its numbers having plunged catastrophically in recent decades. This enchanting little owl, and its curious bouncing song, have become vanishingly rare across much of the coast. Surprisingly, in the not-so-distant past, the Western Screech-Owl was actually the most commonly encountered owl in Vancouver and Victoria, found in city parks, golf courses, and even home gardens.

Ancient Redcedar Grove where a screech-owl was detected.

Many people attributed their subsequent decline to the arrival of the Barred Owl, an opportunistic, highly successful eastern species that had managed to cross the prairies and colonize BC. The role of Barred Owls in the decline of their little cousins remained murky, especially because their presence in BC was a part of a larger story of native ecosystem disruption and alteration that had enabled the Barred Owls to dramatically expand their range. Concurrent with the rise of Barred Owls has been the destruction of BC’s native old-growth forests.

Whatever the reason for the screech-owl’s collapse, the trend has been overwhelming. In a few short decades, screech-owls declined by over 90% in the Lower Mainland and south island. Like little candles flickering out, their voices went silent in the parks and forests that once harboured them. By the mid-2000s, it was far more common in Vancouver to encounter a Snowy Owl wandering down from the Arctic or a vagrant Great-Grey Owl from the boreal forest than to catch a glimpse of what had formerly been coastal BC’s most abundant owl.

Occasional sightings continued to trickle in from up and down the coast, suggesting these owls still held out in isolated pockets, but research on them was woefully lacking. Things changed in 2016 when an undergraduate student at Simon Fraser University named Jeremiah Kennedy set out to solve the mystery. In the forests around the community of Bella Bella, in the territory of the Heiltsuk people in BC’s Great Bear Rainforest, he surveyed for screech-owls. His results were stunning. Though screech-owls were indeed absent from the upland second-growth forests in the region (though Barred Owls were common there), in the old-growth cedar forests that grew in the lowland bogs, screech-owls were abundant! It was like he had gone back in time.

Subsequent surveys suggested that screech-owls were also hanging on in the old-growth cedar forest of northern Vancouver Island. Then in 2020, screech-owls were detected in the contested old-growth forests around Fairy Creek, creating a media firestorm. An owl that had declined by 90% in core parts of its range was suddenly being detected in old-growth forests across the BC coast. A research organization called the Pacific Megascops Research Alliance (Megascops Kennicoti is the scientific name of the Western Screech-Owl), led by the same Jeremiah Kennedy, started to engage government groups and non-profit organizations to work together to understand the habitat needs of this threatened bird.

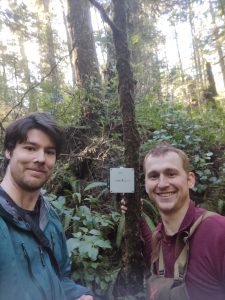

Ian and Jeremiah deploying automated recording units to see if Western Screech-owls can be detected in this forest.

Intrigued by the potential link between screech-owls and old-growth forests, the Ancient Forest Alliance (AFA) reached out to the owl researchers to see how we could collaborate with them on their work. We helped them identify old-growth study sites, contributed our own knowledge about forest structure and ecology, and offered to participate in some of their projects. Because the AFA is so familiar with the Port Renfrew area, we were able to contribute our local expertise about potential screech-owl habitats in this region. We identified a large block of old-growth redcedar forest that we believed represented the best potential habitat for screech-owls. Unfortunately, further research revealed that this block of the forest was riddled with proposed cutblocks. If there were indeed screech-owls holding out in these forests, they were in imminent danger of losing their habitat.

We discussed our ideas with the owl researchers and together we decided to deploy automated recording units into these threatened forests to assess whether screech-owls were present. And that brings us full circle as to why Jeremiah and I were clambering through dense, damp shrubs and criss-crossed deadfall to deploy these recorders. Nothing is more therapeutic than a challenging bushwhack through an old-growth forest: slithering, crawling, climbing, and tumbling through a world so overstuffed with living things energizes the soul while it exhausts the body.

Our pleasure was always tempered though by the cutblock flagging ribbon that popped up everywhere we went. Ancient redcedars were marked for logging and there were lines of flagging ribbon showing where roads would be blasted right through delicate streams. At one big old cedar, we came across the opening of a bear den. We could see the trampled salal leading to a crack in the cedar where a black bear had spent the winter and maybe even given birth to cubs, warm and safe in the hollow heart of this ancient tree.

Passed through this second-growth plantation to access the final study spot looking for Western Screech-Owls.

To access our final study site, we had to cross through a second-growth plantation. This bleak forest was typical of the young forests that now cover much of coastal BC: a plantation of densely stocked young trees with almost nothing growing in the understory. Such forests tend to be near-biological deserts, lacking the species and forest characteristics that define intact old-growth ecosystems.

We pressed on through the gloom of this forest until a green glow ahead of us gave advance notice that we were approaching old-growth again. Everything changed as soon as we set foot in the unlogged forest. We went from the sullen gloom of the second-growth plantation into a green prism of shrubs, ferns, and saplings growing under the thick pillars of old silver firs and hemlocks that combined to create a fully functioning forest community.

Old-growth forest oasis.

We passed deeper into this green oasis and reached the bottom of the hill. Here in the poorly drained flats, the tall, stately hemlocks gave way to twisted old cedars with huge ragged crowns of forking spires. In damp patches, sphagnum moss and fern-leaved goldthread attested to the forest’s boggy character. This spot greatly resembled the old-growth bog forests of Bella Bella where Jeremiah had first found such high numbers of these elusive owls and both of us felt that this place had all the ingredients for ideal screech-owl habitat.

We had been bushwhacking through forests since early that morning and night was starting to fall. After we deployed our automated recording unit, we decided to see if we could detect an owl right then. We crouched on the moss at the foot of a giant cedar and played a recording of a Western Screech-Owl song. After a few minutes of silent listening, we heard our answer: the soft, but distinctive “bouncing-ball” of a singing Western Screech-Owl. Here, in the heart of this ancient grove, was one place where BC’s vanishing owl hadn’t yet vanished.

Western Screech-Owl in the Tsitika Valley.

Those recorders are still out there, quietly documenting the springtime sounds of the forest. Soon we will recover them to analyze the sounds they detected. In the meantime, we have continued to survey for owls in ancient forests on Vancouver Island, finding them in the Tsitika Valley and in the protected refuge of the Carmanah. All of these individual data points will go towards understanding the habitat needs of these threatened birds and what steps are needed to protect them.

Our hope is if we detect screech-owls in proposed cutblocks, we can act quickly to ensure that critical forests are set aside rather than logged into the ground.

The AFA is excited to contribute to our understanding of these rare birds, and we are dedicated to advocating for Western Screech-Owls and all the diverse living creatures that depend on our vanishing old-growth forests for their survival.